About Hilary Boyd

“If you’d have told me, even ten years ago, that I would be a bestselling novelist with my work translated into 23 languages, I would have laughed in your face,’ Hilary says. ‘I absolutely love what I do. And I believe with all my heart, as my books show, that romantic love can strike, at any age. I think it’s so important to have older people – women – represented in fiction. Not just as granny figures, but as vibrant, useful, sexual beings.”

Early Life

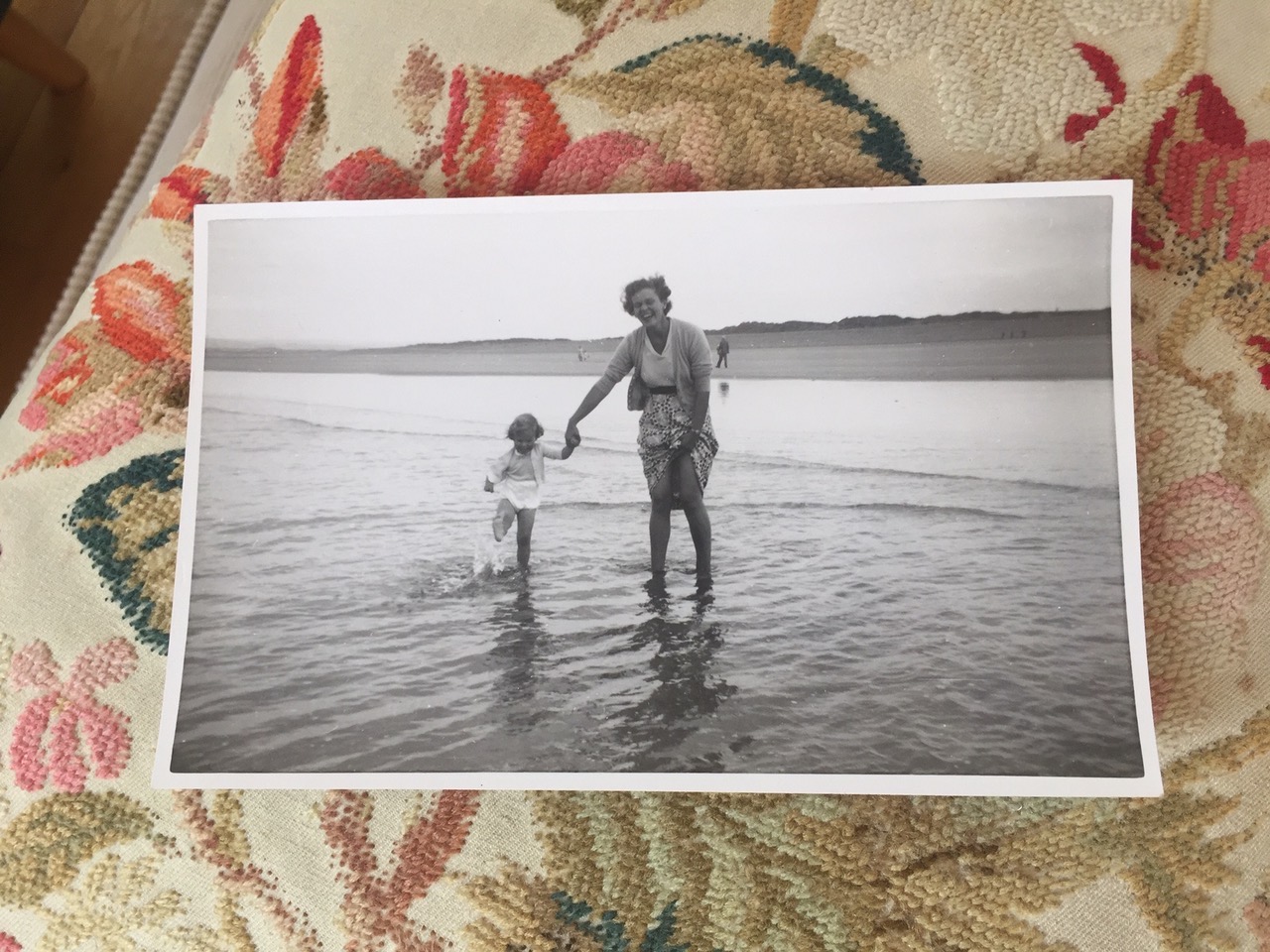

Hilary was born in Prestatyn, North Wales, in 1949, the second child in a family of four. She isn’t Welsh, her parents both came from Liverpool. But her father, Jack, an army major, was stationed in Prestatyn after the war. He was going up Snowdon on a training exercise one day, when he collapsed with a heart attack, aged 30. Jack quickly left the army and they moved to London, where he got a job in advertising. He loved drawing cartoons, sending Hilary funny ones when he was away.

Hilary grew up with a silver spoon in her mouth, in a large house in Knightsbridge, because her mother, Peggy, was the daughter of Fred Marquis, a self-made man from Manchester, who rose very successfully, business-wise, to become Lord Woolton. He was Minister of Food during the war, under Winston Churchill. And responsible for the ‘Dig For Victory’ campaign to get people to grow their own veg, when meat was rationed. Food critic, William Sitwell, recently wrote a book about him, ‘Eggs or Anarchy’.

But despite being well-off, and despite her family being a happy one, her parents very much in love, disaster struck when Hilary was nine. Jack died, aged 42, from a massive heart attack. Her mum’s heart was broken, she never married again. So, Hilary grew up in a single-parent family, with her elder sister and two younger brothers. ‘I remember the day after Daddy died,’ Hilary says. ‘I went to school as usual. I recited the poem I’d learnt for homework in front of the class. And I thought, I’m different from all of you, now. But none of the teachers said a word. Nor did I. It was as if it never happened.’

Disaster struck a second time for Hilary and her family. Her brother John, 3 years younger, developed bone cancer when he was 13, and died an agonising death when he was 15. ‘All the adults said he would be all right,’ Hilary says, ‘but he was skin and bone, in terrible pain, and I knew that he was dying.’

Education

This is what prompted Hilary to train to be a children’s nurse at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH). An unusual career for a posh girl – Hilary was supposed to marry a banker and have four kids, two Labradors and a Range Rover, live somewhere in the Shires. Her Roedean housemistress was worried at her choice. ‘Won’t you be too tall,’ she asked Hilary, ‘to bend down into the babies’ cots?’ Not a very tactful thing to ask a girl of seventeen, who was painfully self-conscious about her 6 foot frame.

Marriage

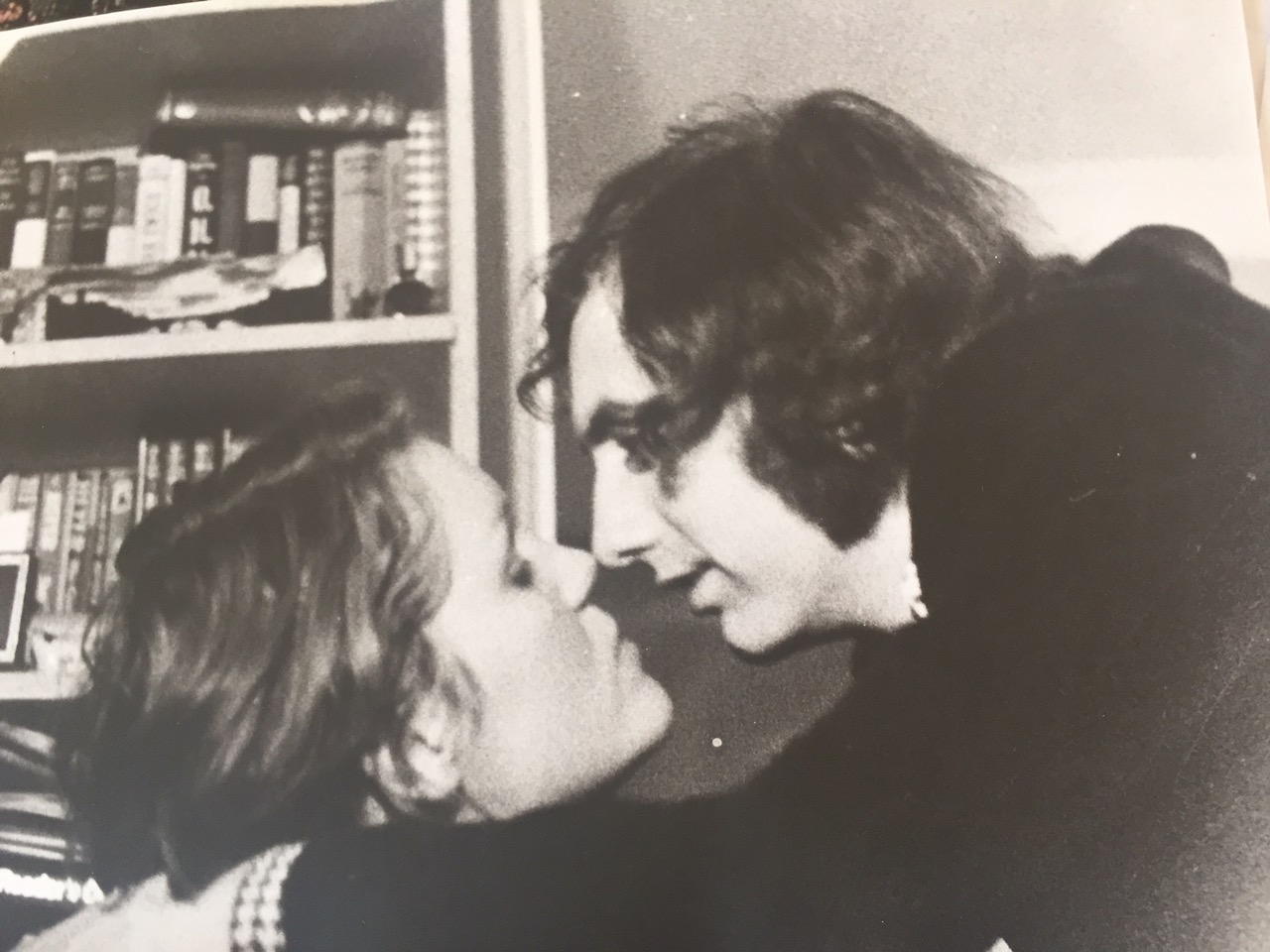

Hilary fell madly in love with Don when she was 22. He wasn’t the expected sober banker, but a film director/producer in a red velvet suit. He already had a daughter from his first marriage, and they went on to have two more. They’ve been married now for 50 years.

Hilary has always been an obsessive reader. She grew up with the romantic novels of Daphne du Maurier and Georgette Heyer, Agatha Christie’s whodunnits. But while she was nursing, she went on a trip to the Canaries with a friend and had a brief fling with a blond, handsome Hungarian/American. He was reading Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s First Circle. Serious stuff.

So, Hilary went home and tried it. She was hooked. Since then she reads everything. Romantic, literary, detective, biography, non fiction… the lot. It never entered her head that she might write herself, though. She wouldn’t have dared. But with Don she was now living in a social group where everyone seemed to write/paint/act/make films. It was almost normal.

Nursing was interrupted by the family move to California. Don was working for a big film studio and they rented a house with a swimming pool in the Hollywood hills, owned by none other than Mel Brooks. Life for Hilary was all about hanging out with actors/directors/producers etc, and talking about movies, movies, movies. ‘It was uber-glamorous, but lonely,’ Hilary says. She missed her friends and family in England, and Don was away shooting a lot.

When they came back to London, Hilary trained to be a marriage guidance counsellor. But she wanted to study. She hadn’t done well at school and left with only a handful of ‘O’ levels – GCSE equivalents – and so took two ‘A’ levels in evening classes. Then one day a friend suggested she go to University. ‘Don’t be ridiculous, I’d never get in,’ Hilary insisted. But she applied as a mature student – then 36 – and, much to her surprise, got a place at London University – Holloway and Bedford College, in Egham – to study English Literature.

Family

The next period in Hilary’s life was grim and chaotic. Three children at home, aged 8, 11 and 14, (her stepdaughter was living with them now), a college course to complete, her much loved mum dying – she’d been suffering from MS for years and now had cancer – and Don often away on film business. ‘I was going crazy, rushing from school drop off to college, college to school pick-up, on to poor Mum’s,’ Hilary says. ‘The other students would lounge around, writing their essays at the weekends. I didn’t have weekends. So, I would shut myself in the bathroom and read the complete works of Charles Dickens, the kids banging on the door for supper!’

Hilary got her degree, a respectable 2:1. The tutors often said of her essays, ‘The content is sometimes patchy, but you do write well.’ And after college, writing took over Hilary’s life. She did journalism at first, such as reviewing Mind, Body, Spirit books in a column for the Daily Express, then moved into factual, how-to books. They were about step-parenting, ways to treat depression, pregnant women’s rights in the workplace, a pregnancy book with TV presenter, Melanie Sykes.

Writing

And all the while, Hilary, in any spare moment, was beavering away at her first romantic novel. ‘It wasn’t any good,’ Hilary says, ‘but at least it got me an agent.’ The unpublished romances piled up over the next 15 years – Hilary admits to 5. She got another agent – a very patient one – who sent out her manuscripts with endearing enthusiasm each time. The publishers’ emails came back, always the same: Not enough dialogue, too much depressing navel-gazing, weak heroine. But Hilary writes well. Oh, the frustration!

Freelance writing and making films make for a precarious existence at the best of times, and the Boyds were often broke. Over the years, Hilary took many different jobs, ranging from working as a private nurse, for an engineering company, an online vitamin company, and running a small cancer charity. But always writing another love story…

And then one sunny summer’s day, Hilary turned 60. The shock was extreme. She found it hard to believe that she could now be seen as ‘old’, termed a Senior Citizen. Granny glasses and a perm, slippers by the fire? ‘It galvanized me,’ Hilary says. ‘I remember thinking, it can’t all be over.’

Every Thursday, she would take her little granddaughter – the apple of her eye – to the local park in Highgate, where they were now living. That particular day, Hilary was pushing her granddaughter on the swing – back and forth, back and forth, the child was obsessed – and gazing across the small playground. There was an older man, guiding his little boy – son or grandson? – down the slide in the far corner. And Hilary had a light-bulb moment. What about a love story, she thought, where two older people – not thirty-somethings for a change – meet in the playground with their grandchildren… and fall in love?

This time, Hilary properly listened to the previous criticism of her work. Her heroine would be the strongest, most sympathetic character in the whole of romantic fiction – she based it on a good friend’s amazing mother. The novel would be full to the brim with dialogue. She wouldn’t have even a sniff of navel-gazing.

Hilary wrote Thursdays in the Park in only a few months. It poured out of her. And her delighted agent loved it. But it was about older people falling in love. ‘I honestly didn’t think anyone would go for it,’ Hilary said. ‘Wouldn’t there be the ‘eugh factor’ about people in their sixties having… sex?

Apparently not. Quercus was the first publisher Hilary’s agent sent the manuscript to. And she was immediately offered a two-book deal. ‘I’ve often heard the phrase, ‘walking on air’, but I actually was,’ Hilary says. ‘Two feet off the ground at least. It was an extraordinary feeling. I just could not believe it.’ My brilliant editor, Jane Wood, didn’t want too many changes. She just wanted to know that my heroine and her lover had actually done the dirty deed. She said it wasn’t quite clear. And Hilary had to bite the very tricky bullet and write her first sex scene.

Bestselling Writer

So, Hilary Boyd’s love story was published. One great review in the Daily Mail, not much else. Sold around three thousand copies. Not terrible, but not great either. Then, a year after it hit the book shops, a strange thing happened. Hilary, as an ingenue novelist, had thought that was it for Thursdays. She was disappointed, but was already cracking on with her next book. Then she got an email from Quercus. ‘Thursdays is number 17 in the Amazon e-book bestseller chart’, it said.

Flabbergasted, Don and Hilary watched it creep up to number 11, then 7 – in the top ten?? – then… wait for it, number 1. They became obsessed. Don called it ‘Amazon porn’. It stayed there and sold over half a million copies. Robert McCrum, a journalist at the Observer at the time, picked up the story, and did a long article, coining the phrase, ‘Gran-Lit’. And suddenly everyone wanted to know. Hilary was called by papers and radio shows all over the country, and as far afield as Sweden and Germany. She was even featured on the Today Programme, and ITV’s News at Ten.

But nobody really knows what sparked the success, after a year of selling comparatively few copies.

Hilary’s life changed radically from that moment. She was able to give up her two day jobs and be what she had never in a million years thought she could be: a full-time romantic novelist. She has gone on to write 7 more love stories about older people and is currently awaiting publication of her 9th in February 2020: The Lie. She is now published by Michael Joseph at Penguin Books.

‘If you’d have told me, even ten years ago, that I would be a bestselling novelist with my work translated into 23 languages, I would have laughed in your face,’ Hilary says. ‘I absolutely love what I do. And I believe with all my heart, as my books show, that romantic love can strike, at any age. I think it’s so important to have older people – women – represented in fiction. Not just as granny figures, but as vibrant, useful, sexual beings.’

Q & A

A conversation with the writer.

1. Where do you write?

I have a cosy room in the attic of our house. It has windows overlooking the road through the village and the roof tops, so when I’m bored I can gaze out and watch the world go by. My husband is across the patio in the converted garage, so we can’t hear each other thinking! This is a vast improvement to our tiny London flat, where we were on top of each other, driving each other nuts.

2. What is your writing routine?

Sorry, I’m not one of those writers who’s hard at it by 5am. Nor do I write long into the night. My routine is really dull, like a 9 – 5. My best time is the morning. Then after lunch I’ll revise – often junk – what I wrote earlier, and get depressed about what rubbish it all is. I’ll have a cuppa and go for a long walk round the harbour at the end of the day – ten minutes away – and breathe out all the tension in the peaceful beauty. It’s a pretty bloody lovely routine, I reckon.

3. How did you start writing about romance?

I’m a true romantic. I’ve always been a sucker for a great love story. Who isn’t? The whole relationship dynamic fascinates me – I suppose that’s why I became a marriage guidance counsellor – and there’s so much emotion in a love affair. You can go for broke. Really feel it.